Anche se non ama questo termine, Jan Noble è un poeta performativo: in altre parole, preferisce recitare le sue poesie davanti a un pubblico dal vivo piuttosto che pubblicarle sulla carta stampata. Le sue poesie sono lunghi pezzi, della durata di circa 40 minuti e, quando le legge sul palco, l’esperienza è teatrale. La sua ultima opera, Shelley 200, un tributo personale a Percy Bysshe Shelley, il poeta romantico inglese annegato vicino a La Spezia nel 1822, è attualmente in tournée in Italia. Jan l’ha recentemente eseguita all’Après Coup di Milano e alla leggendaria Keats Shelley House (dove un altro poeta inglese, John Keats, morì di tubercolosi nel 1821) a Roma. In questa conversazione con Laura Davì e Mark Worden – che firma la traduzione in inglese – parla della sua poesia, del suo insolito rapporto con l’arte visiva e del rapporto che ha con l’Italia.

Jan Noble – Il mio primo viaggio in Italia è stato quando ho frequentato per un mese una scuola estiva vicino a La Spezia, a Portovenere, sull’Isola Palmaria con altri studenti d’arte provenienti da Germania, Italia, Inghilterra e Grecia. Era gestita dall’Accademia di Belle Arti di Berlino e il catering era curato da una coppia di italiani: la moglie cucinava e il marito non faceva altro che starsene seduto, fumare e bere. Fu quella la mia introduzione ai poeti inglesi in Italia. Eravamo nel Golfo dei Poeti quando questo marito pigro mi disse: «Oh, devi sapere di Shelley, che è annegato qui». In quel momento, essendo uno studente di arte, non sapevo nulla di poesia, ma ad attirarmi era il fascino di questi personaggi, più che quello che scrivevano. Chi erano questi ragazzi? Cosa facevano qui? Perché erano venuti qui? Come sono finiti a morire qui? È stata la vita dei poeti, più che quello che hanno scritto, ad attirare la mia attenzione.

Laura Davì, Mark Worden – Hai studiato arte e sei un poeta.

JN – Sì, ho studiato arte, non provengo affatto da una formazione accademica, ma c’è una tradizione di poeti e scrittori che escono dalla scuola d’arte. Il poeta irlandese W.B. Yeats non era accademico, era dislessico, non si applicava a scuola e ha frequentato la scuola d’arte, come suo fratello diventato pittore. Solo circondandosi di arte ha trovato la musica e il lirismo.

LD, MW – Pensi che ci sia un parallelo con le varie rockstar degli anni Sessanta e Settanta che uscivano dagli istituti d’arte?

JN – Assolutamente sì. Molto fuori moda, negli anni Ottanta ero un fanatico dei Beatles. Ho saccheggiato la collezione di dischi di mio padre e ho trovato incredibili album in vinile, Sgt. Pepper e The White Album, due dischi straordinari che mi attraevano dal punto di vista dei testi, piccole mini opere, canzoni sensazionali. She’s Leaving Home, il gioco di parole lirico, la sottigliezza del linguaggio, la semplicità, la bellezza di tutto questo, e suppongo anche il packaging. Così, da adolescente, mi sono appassionato ai Beatles e poi ho scoperto che John Lennon aveva frequentato la scuola d’arte e ho deciso di fare come lui. Per un po’ ho anche iniziato a parlare con l’accento di Liverpool e sono andato dal mio parrucchiere di fiducia con una foto di John Lennon dal White Album e gli ho chiesto se potevo avere un taglio di capelli come il cantante. Poi, grazie ai Beatles, ho scoperto i poeti di Liverpool, Roger McGough, Adrian Henri e Brian Patten. Il mio salto nella poesia è avvenuto grazie a Mike McGear, il fratello di Paul McCartney, che cantava nel gruppo The Scaffold con Roger McGough. E dai poeti di Liverpool ho trovato Adrian Mitchell, che non era uno del gruppo ma era associato a loro, e la sua poesia performativa, la più famosa alla Royal Albert Hall nel 1965. Tutto questo mi ha portato ad Allen Ginsberg, e sono partito!

LD, MW – Alcuni editori ti hanno invitato a pubblicare le tue opere in formato cartaceo, ma hai rifiutato. Come mai?

JN – Torniamo ai Beatles. Uno dei primi libri di poesia che ho comprato era un’edizione integrale dei loro testi e sono rimasto molto deluso nel vedere come queste canzoni rappresentate sulla pagina apparissero morte. Tutta la magia era sparita! Non c’era più nulla di magico sulla pagina, e questo mi ha fatto pensare a cosa succede alle parole se rappresentate con un inchiostro morto. Quando ho ascoltato per la prima volta Under Milk Wood di Dylan Thomas, ho sentito la poesia resa come un gioco di voci e ho capito che avevo bisogno di presentare il mio lavoro così. Il mio consumo di poesia è, per lo più, fuori dalla pagina, fuori dai libri.

Mi affascina anche l’idea della riverenza per la pagina stampata nell’era digitale. Nel Regno Unito, quando si dice di essere un poeta, la prima domanda è: «Oh, sei pubblicato?». Apparire in un libro è un sigillo di approvazione e di autorità.

Un’altra grande influenza per me è stata T.S. Eliot, che si è davvero auto-pubblicato. The Waste Land è uscito in una rivista che ha fondato lui stesso e ha pubblicato le sue poesie presso Faber, dove era editore.

Per me l’impatto della parola detta è unico ed è ciò che mi interessa esplorare. Non ho nulla contro la poesia su carta stampata, ma al momento sono più interessato a mantenere viva l’opera.

Body 115 è un mini dramma in versi, un racconto di viaggi interiori ed esteriori in esplicito omaggio alla Divina Commedia di Dante scritta e interpretata Jan Noble (dal sito dell’autore).

LD, MW – Abbiamo avuto il piacere di assistere alla tua lettura di Shelley 200 e, pur non avendo una padronanza totale della lingua inglese che permettesse di capire del tutto il testo, siamo stati colpiti dalla performance. L’impatto è forte anche senza comprensione verbale.

Jan Noble legge l’opera Shelley 200 [Prima parte]

JN – Sì, John Keats una volta disse che non si deve necessariamente capire una poesia ma che bisogna viverla. Faceva un’analogia con l’immersione in un lago: non si capisce la sensazione, la si sperimenta. Può capitare anche di aprire un libro e trovare quella magia sulla pagina, leggendo una poesia. Ho letto Sylvia Plath per la prima volta in una pagina stampata ed è stata un’esperienza. Questa è la bellezza e la flessibilità della poesia, che non è fissata a un punto particolare, ma è una forma d’arte fluida.

LD, MW – Performando le tue poesie, lasci aperto anche l’immaginario.

JN– La parola immaginario compare come salvaschermo sul pc di Carlo Rea, artista amico e figlio del compianto giornalista Ermanno Rea. Ho avuto così l’occasione di tentarne con lui un’interpretazione semiotica analizzando la parola stessa. Siamo arrivati a In me agisce il mago, il magico.

Nella parola immaginario vedo dunque collegate immagine e magia. Si tratta di creare magia con le immagini e questo è davvero il mestiere della poesia. Mi piace anche l’idea del fare. In Scozia e in Galles i poeti fanno poesia, non la scrivono. T.S. Eliot dedica The Waste Land a Ezra Pound, una figura molto controversa, e lo chiama “iI miglior fabbro”, il miglior artigiano o creatore. Penso che ci sia un senso di costruzione o di edificazione, ma c’è una magia anche in questo, nel modo in cui metti insieme i mattoni, nel come li assembli e crei qualcosa che è dell’immaginazione, ma è anche una costruzione. Il mio vecchio agente, Don Mousseau, purtroppo scomparso qualche mese fa, una volta disse, quando qualcuno commentò che le mie poesie erano costruite: «Jan non è solo l’architetto delle sue poesie, è anche la loro architettura». Questo si ricollega a ciò che dicevamo a proposito dell’editoria: se si vuole la poesia, allora si invita il poeta, per avere una totale corrispondenza.

LD, MW – Nella tua recente performance milanese, Shelley 200, sembrava che non stessimo solo ascoltando una poesia, ma che stessimo anche guardando una poesia, più che un poeta. Per questo è così potente, è uno strano mix. Tu sei la poesia.

JN – Credo che questo si ricolleghi a ciò che dicevo prima, cioè che all’inizio ero più interessato ai poeti e alle loro vite che alla loro poesia, a una certa idea del vivere poeticamente. Alla scuola d’arte i professori si riferivano molto alle performing arts degli anni Settanta. Un altro libro che avevo era Coyote di Joseph Beuys, una serie di fotografie che raccontavano di quando l’artista aveva vissuto in una galleria d’arte con un coyote, diventando un animale per una settimana. Il libro non restituiva quello che era l’opera d’arte, che era un essere vivente, un’installazione. Sono molto interessato alle differenze tra un poeta, il poema e la poesia.

LD, MW – Forse la poesia è come la musica, è bella da ascoltare, ma non si può dire cosa significhi, anche se si sente qualcosa quando la si ascolta.

JN – C’è un verso in una poesia di Adrian Mitchell, The Oxford Hysteria of English Poetry, in cui dice dei Normanni: «Ormai tutti cominciavano a scrivere poesie, risparmiando la memorizzazione e l’improvvisazione, e i contadini non riuscivano ad averne accesso». Quando la poesia inizia a essere scritta, comincia anche a essere riservata a coloro che sono in grado di leggere e scrivere, ma prima di allora la poesia era per tutti. Per via di questa separazione la poesia diventa quindi accademica ed elitaria: esiste ancora oggi il pregiudizio per cui la poesia non è “per me”, è qualcosa che solo le persone “intelligenti” possono capire e interpretare. Ma la poesia è anche immaginario, comprende la magia e il mistero e non è qualcosa che deve essere necessariamente compresa. Ecco perché l’analogia con la musica è meravigliosa, perché in lei trovi il feeling. Quando ascolti una sinfonia di Mahler non è che poi vai automaticamente a comprare lo spartito, a cercare i punti bianchi e neri su una pagina. Per me, la pagina stampata è lo spartito della poesia.

LD, MW – Allo stesso modo, molta arte contemporanea ha bisogno di essere sentita piuttosto che compresa.

JN– Penso che l’arte contemporanea però sia stata sequestrata da critici intellettuali che dicono «Sì, capisco cosa l’artista sta cercando di fare». E che l’arte, come la poesia, debba invece essere sentita. Questo è in parte il motivo per cui sono interessato al periodo romantico, perché è lì che i sentimenti sono venuti alla ribalta. Non è una ricerca intellettuale, i poeti cominciavano a parlare di ciò che sentivano.

Ho trascorso molto tempo a lavorare negli ospedali psichiatrici insegnando la poesia ai pazienti e ho imparato molto sul sentimento e sulla follia. Mi è venuto in mente il luogo in cui John Keats è cresciuto a Londra, vicino all’ospedale psichiatrico originale di Bethlehem, o Bedlam, a Moorfields, dove c’erano due enormi statue dedicate a Malinconia e a Delirio, che erano due disposizioni della follia. E vedo Allen Ginsberg che delira mentre legge Howl nella famosa International Poetry Incarnation, lettura di poesie del 1965 alla Royal Albert Hall di Londra, mentre la malinconia è la disposizione che tendiamo ad associare alla poesia.

Sono sicuro che Keats fosse molto consapevole di queste statue mentre cresceva, e ha esplorato questi temi nella sua poesia.

LD, MW – Ad accompagnare Shelley 200 c’è anche un video. Ce ne puoi parlare?

Shelley 200 è il nuovo monologo poetico che Jan Noble dedica alla vita e all’opera di Percy Bysshe Shelley. Le letture a Londra, al memoriale del poeta a Viareggio e al Festival Internazionale Teatro Romano di Volterra hanno preceduto una performance speciale tenutasi alla 22a edizione di Poetry on The Lake a Orta, Italia e alla Keats-Shelley House di Roma. Video by Giulia Vannucci.

JN – Giulia Vannucci è una film-maker italiana con cui ho collaborato per il progetto del video di Shelley 200, di cui ha prodotto le immagini. Realizza ritratti video di fotografi, ha una passione per il cinema e per il periodo romantico, in particolare per il pittore paesaggista inglese William Turner. Giulia ha creato questa straordinaria atmosfera di paesaggio marino/celeste, molto alla Turner, e ha avuto l’idea di tentare l’esperimento della pubblicazione di una poesia con testo e immagini. Abbiamo parlato molto di William Blake e dei suoi libri, del modo in cui combinava testo e immagine e di quanto sia difficile mettere insieme le due cose. È l’inizio di una collaborazione tra un poeta e una regista e questo è stato il nostro primo tentativo di realizzare una video-poesia, qualcosa che vogliamo continuare a esplorare. Per me sono entrambi basati sul tempo, con un inizio e una fine, sono in dialogo con la fascinazione di Giulia Vannucci per l’immagine fissa e quella in movimento e con il modo in cui le poesie hanno punti di immobilità e sono punteggiate da singole immagini. Sono come una fotografia.

Anche l’aspetto anglo-italiano è interessante. Ho conosciuto Giulia, originaria di Lucca, quando ho partecipato a una lettura di 24 ore di Dante a Firenze per il 700° anniversario della sua morte, su cui la regista ha realizzato un film. Io vengo da una scuola d’arte inglese, una specie di rock’n’roll incasinato, mentre lei ha una base molto solida nei classici, un approccio molto diligente, ed è interessata a quello che considera la roccia piovosa delle isole britanniche e alla turbolenza che lì creiamo: i dipinti di Turner, le espressioni e le esplosioni di Shelley e il punk rock, provengono tutti da lì. Io vedo l’Italia come un museo dell’antichità, il paese di Dante e del Rinascimento: anche questo è un matrimonio. E il film che ha realizzato è come un libro, le onde sono come pagine che si sfogliano.

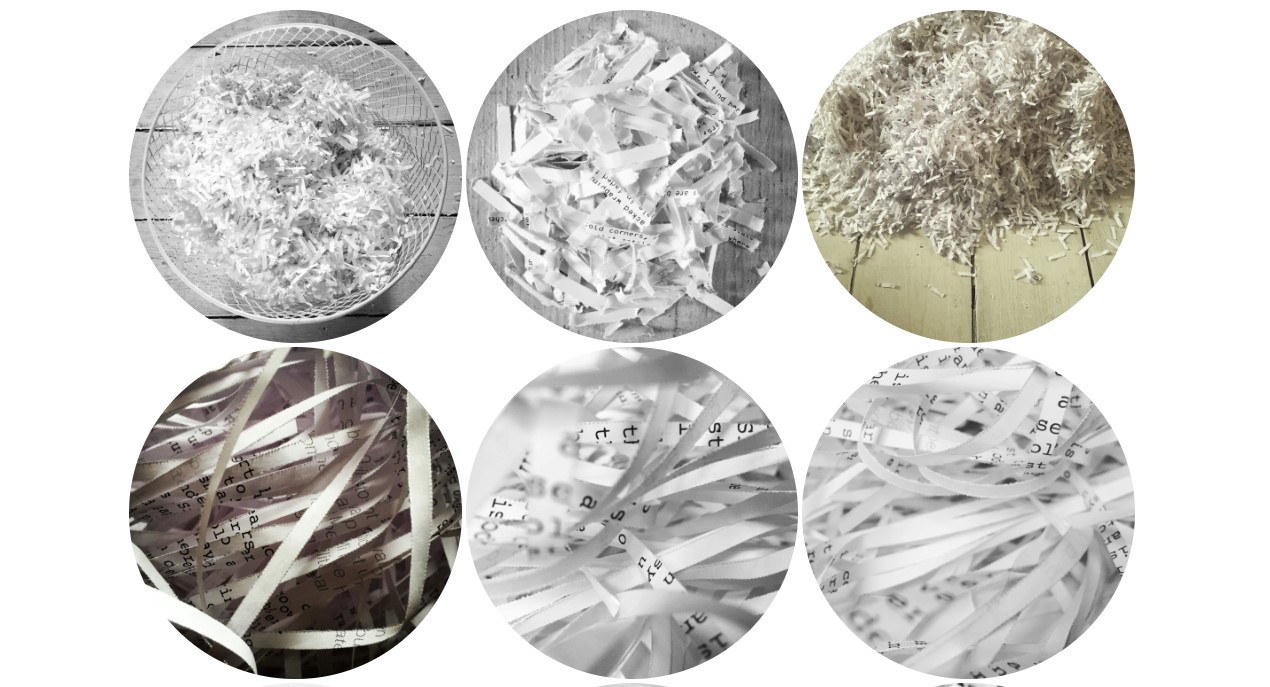

LD, MW – Il tuo sito web ha una sezione molto interessante chiamata Opere rifiutate con foto di parole scartate, che potrebbero per me essere una mostra fotografica e che trattano anche il tema del fallimento. Da dove nasce questa idea?

JN – Il mio sito web aveva solo due pagine: Opere selezionate e Opere rifiutate. Quando frequentavo la scuola d’arte amavo i vecchi provini a contatto e un’immagine che mi colpì molto fu quella di Paul Simonon dei Clash che nell’atto di spaccare una chitarra posta sulla copertina di London Calling. Mi chiedevo quante immagini ci fossero in quella sequenza e quale fosse quella scelta per quella iconica copertina dell’album. Mi affascina anche l’idea di quante versioni ci siano di una poesia. Non si tratta solo di uno sputo, ed è tutto lì. Quando si guardano i manoscritti dei poeti, alcuni sono immacolati e la poesia scorre, mentre altri balbettano e si bloccano, ci sono cancellature, disegni a margine e scarabocchi. C’è una certa fatica, che si rifà all’idea del “fare” una poesia. Il mio vecchio agente mi disse che non avrei dovuto pubblicare queste poesie perché mostrano il fallimento e io risposi che non si trattava di fallimento, ma di processo. Credo che ci piaccia che le cose vengano presentate come articoli finiti, ma l’esecuzione di una poesia è sempre diversa e nella poesia c’è molto lavoro che non si vede. Non si tratta sempre di miseria, fallimento e rifiuto, c’è una bellezza in questi piccoli frammenti. Per esempio, di recente ho preso un verso da una poesia che avevo scritto e rifiutato dieci anni fa e l’ho usato in una nuova poesia. È come quella piccola immagine dei provini a contatto: tienila per la prossima volta!

LD, MW – Shelley può avere ancora importanza ai giorni nostri?

JN – Shelley ha ancora rilevanza nel mondo d’oggi insieme al gruppo di poeti morti in anni molto ravvicinati, Keats ad esempio, tra cui vorrei includere Mary Shelley. Shelley ha portato avanti una voce di protesta politica e lo vedo molto attivo ad esempio in Black Lives Matters. I suoi poemi di protesta hanno dato ai poeti potere politico.

LD, MW – Ritieni di avere anche tu con la tua poesia questo ruolo politico?

JN – Questo ruolo politico l’ho avuto anch’io all’inizio, ma ora ci sono troppe opinioni e nessun discorso e la poesia dovrebbe guardare altrove. Per me la poesia riguarda il linguaggio, come dici più di cosa dici. Oggi viene affidata molta enfasi al messaggio mentre preferisco occuparmi della forma con cui questo si veicola, più che del messaggio stesso. Il linguaggio è stato ridotto e nell’era di Twitter e, oserei dire, attraverso i mass media dove l’opinione è regina. La poesia ci permette di reinventare come parliamo del mondo, un processo attraverso il quale potremmo trovare una voce fresca con cui offrire nuove opinioni.

Di seguito la traduzione in inglese dell’intervista a cura di Mark Worden.

Jan Noble: the art of poetry

Laura Davì with Mark Worden

Even though he doesn’t like the term, an Noble is a performance poet: in other words, he prefers to perform his poetry in front of live audiences rather than publish it on the printed page. His poems are longer pieces lasting about 40 minutes and, when he reads them on stage, the experience is theatrical. His latest offering, Shelley 200, a personal tribute to Percy Bysshe Shelley, the English Romantic poet who drowned near La Spezia in 1822, is currently touring Italy. Jan recently performed it at Après Coup in Milan and at the legendary Keats Shelley House (where another English poet, John Keats, died of tuberculosis in 1821) in Rome. In this conversation with Laura Davì and Mark Wonder he talks about his poetry, its unusual relationship with visual art, and his own relationship with Italy.

Jan Noble – My first trip to Italy was when I came to a summer school near La Spezia at Portovenere, on the Isola Palmaria. It was run by the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts and there were art students from Germany, Italy, England and Greece on this little island for a month. The catering was by an Italian couple: the wife cooked and the husband did nothing apart from sit around, smoke and drink, but that was my introduction to the English poets in Italy because it was Il Golfo dei Poeti and this lazy husband said, “Oh, you must know about Shelley, who drowned here”. At that point, being an art student, I didn’t know anything about poetry, but at the beginning it was the fascination with these characters, rather than what they wrote, that appealed to me: Who were these guys? What were they doing here? Why did they come here? How did they end up dying here? It was the lives of the poets, rather than what they wrote, that initially attracted my attention.

Laura Davì, Mark Wonder – Please tell us more about your life as an art student.

JN – Yes, I studied art, I don’t come from an academic background at all, but there is a tradition of poets and writers coming out of art school. The Irish poet W.B. Yeats was not academic, apparently. He was dyslexic, he didn’t apply himself at school, and went to art school, like his brother, who became a painter, and it was only at art school that he found this music, this lyricism, by being surrounded by art.

LD, MW – Do you think there’s a parallel with the various rock stars of the 1960s and 1970s who came out of art college?

JN – Absolutely. Very unfashionably, in the 1980s I was a Beatles nut. I raided by dad’s record collection and found these incredible vinyl albums like Sgt. Pepper and The White Album, these two amazing records and they appealed to me lyrically, these little mini operas that they wrote, these sensational songs: She’s Leaving Home, the word play, the lyrical word play, the subtlety of the language, the simplicity of it, the beauty of it all, and I suppose the packaging as well. And so, as a teenager, I became wildly interested in the Beatles, and then found out that John Lennon had been to art school and so that was how I was going to go forward, I was going to follow John Lennon. I even started talking with a Liverpool accent for a while, and I went down to my local hairdresser with a photograph of John Lennon from The White Album and asked him whether I could have a hair cut like this, and this wonderful Jewish barber at the end of our street just said, “I’m afraid I can’t cut your hair like that as you haven’t got enough of it!” Basically, I had a schoolboy haircut. And then, from the Beatles, I found the Liverpool poets like Roger McGough, Adrian Henri and Brian Patten. My jump into poetry was via Mike McGear, Paul McCartney’s brother, who sang in the group The Scaffold with Roger McGough. And from the Liverpool poets I found Adrian Mitchell, who wasn’t a Liverpool poet, but was associated with them, and his performance poetry, most famously at the Royal Albert Hall in 1965, and this led me to Allen Ginsberg, and I was off!

LD, MW – I believe that publishers have invited you to publish your work in print, but you have turned them down. Why is that?

JN – I’m taken back to the Beatles. One of the first poetry books I bought was the complete lyrics of the Beatles and I was really disappointed by seeing these songs represented on the page and how dead they appeared. All of the magic had gone, there was no magic on the page, and that made me think about what happens to words when they are rendered in dead ink. And when I heard Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood for the first time, when I heard poetry rendered as a play for voices, it just made sense, that this is how I needed my work to be presented. My consumption of poetry is, in the main, off the page, from books. I’m also fascinated by this idea of reverence for the printed page in the digital age. Certainly in the UK, whenever you say you’re a poet, the first question is, “Oh, are you published?” Appearing in a book is a seal of approval and a stamp of authority. Another great influence for me was T.S. Eliot, who was effectively self-published. He published The Waste Land in a magazine that he started, he published his poetry at Faber, where he was an editor. For me the impact of the spoken word is unique and I’m more interested in exploring that. I’ve nothing against poetry on the printed page, but at the moment I’m more interested in keeping the work alive.

LD, MW – Some members of an Italian audience might not understand your poetry, but it still has a strong impact on them.

JN – Yes, John Keats once said that you don’t necessarily have to understand a poem: you must experience it. He drew an analogy with diving into a lake: you don’t understand the sensation, you experience it. You can have that magic reading a poem: I read Sylvia Plath for the first time on the printed page and it was “an experience”, it can be an event to open up a book and find that magic on the page. This is the beauty and the flexibility of poetry: it isn’t fixed to a particular point. It is a fluid art form.

LD, MW – By performing your poetry you also leave the Immaginario open.

JN – The best definition of Immaginario I have heard is by a friend of mine, the artist Carlo Rea, who is the son of the late journalist Ermanno Rea, and that is “In me the magician acts”. In the word “Immaginario” I see “image” and “magic” as being linked. It’s about creating magic with images and that really is the business of poetry: “Shall I compare thee to summer’s day?” I also like the idea of “making”: in Scotland and Wales poets “make” poetry, they don’t write it. At the beginning of The Waste Land T.S. Eliot dedicates it to Ezra Pound, a very controversial figure, and calls him “Il miglior fabbro”, the better craftsman or maker. I think there is a sense of construction or building, but there is a magic in that, in the way you put the bricks together, the way you assemble that and create something of the imagination, but it is a construction. My old agent, Don Mousseau, who sadly passed away a few months ago, once said, when someone commented on my poems being constructed, that “Jan is not just the architect of his poems, he is their architecture as well.” This goes back to what we were saying about publishing: if you want the poem, then you invite the poet, in order to get the full complement.

LD, MW – At your recent Milan performance it felt as if we weren’t only listening to a poem, but we were also watching a poem, rather than a poet. That’s why it’s so powerful, it’s a strange mix. You are the poem.

JN – I suppose it goes back to what I was saying before about at first being more interested in the poets than their poetry. Another book I had was Joseph Beuys’s Coyote, a series of photographs about the time when he lived in an art gallery with a coyote, and he became an animal for a week. And the book wasn’t what the art piece was, which was a living thing, an installation. I’m very interested in the differences between a poet, the poem and poetry.

LD, MW – Perhaps poetry is like music – it’s beautiful to listen to, but you can’t say what it means, although you feel something when you listen to it.

JN – There’s a line in a poem by Adrian Mitchell, The Oxford Hysteria of English Poetry, where he says of the Normans “by now everyone was starting to write down poems, well, it saved memorizing and improvising And the peasants couldn’t get hold of it.” Poetry then became elitist, something that only “clever” people could understand and interpret, but it doesn’t have to be understood. That’s why the music analogy is wonderful. When you hear a Mahler symphony you don’t automatically go out and buy the sheet music. For me, the printed page is the sheet music of poetry.

LD, MW – Similarly, a lot of contemporary art needs to be felt rather than understood.

JN – I think contemporary art has also been hijacked by intellectual critics who say: “Yes, I see what the artist is trying to do.” I think art, like poetry, should be felt. That’s partially why I’m interested in the Romantic period because that’s when feelings came to the fore. It’s not an intellectual pursuit. Poets were beginning to talk about how they felt. I spent a lot of time working in and around psychiatric hospitals as I would teach poetry to patients. I became very aware of that area of feeling and madness and where it all came from. And I was reminded of where John Keats grew up in London, near the original Bethlehem, or Bedlam, mental hospital in Moorfields, and it featured two enormous statues of “Melancholy” and “Raving”, which were two dispositions of madness. And I can see Allen Ginsberg “raving” as he reads Howl at the famous 1965 poetry reading in the Albert Hall, while melancholy is the disposition that we tend to associate with poetry. I’m sure Keats was very aware of these statues as he grew up, and he explored these themes in his poetry.

LD, MW – The video that accompanies Shelley 200 is wonderful. Please could you tell us about this collaboration?

JN – Yes, sure. Giulia Vannucci is an Italian film-maker and we’ve worked on one big project together, which is the visuals that she provided for the Shelley piece. She makes video portraits of photographers. Her passion is film, but also the Romantic period, particularly the English landscape painter William Turner, and she has created this amazing sort of seascape/skyscape piece, which is very Turneresque. It was a kind of experiment in terms of publishing a poem with text and image. It was her idea. We spoke a lot about William Blake and his books and the way that he combined text and image and how difficult it is to put the two together. So that was our first attempt at making a video poem and it’s something that we really want to explore with subsequent pieces. For me they’re both time-based pieces with a beginning and an end, and her fascination with the still image and the moving image and how poems have points of stillness and are punctuated with single images, which are like a photograph. This is the beginning of a collaboration between a poet and a film-maker. The Anglo-Italian aspect is also interesting. Giulia is from Lucca. I met her when I was involved in a 24-hour reading of Dante in Florence for the 700th anniversary of his death, and she made a film about that, but she has a very solid grounding in the classics. I’m from an English art school-punk-kind of fucked up rock’n’roll background, whereas she has this very diligent approach, which I think comes from the solid foundations of a classical background and she’s interested in what she regards as the rainy rock that is the British Isles and this sort of turbulence that we produce: the paintings of Turner, the expressions and explosions of Shelley and punk rock, they all come from this place, whereas I see Italy as this museum of antiquity, the country of Dante and the Renaissance. So that is also a marriage. The film she has made is also like a book, and the waves are like pages turning.

LD, MW – Your website has a section called “Rejected Works” with photos of mashed up words, and they could almost be a photography exhibition. Where did that idea come from?

JN – My website used to have just two pages: “Selected Works” and “Rejected Works”. When I was at art school I used to love the old contact sheets and one image that really struck me was the one of The Clash’s Paul Simonon smashing a guitar on the cover of London Calling and you wonder how many images there were in that sequence and about the one that was chosen for that iconic album cover. I’m also fascinated by the idea of how many versions there are of a poem. It isn’t just this “blurt” and there it all is. And when you look at poets’ manuscripts, some of them are immaculate and the poetry is just flowing, and there are others where the poetry stutters and it stalls and there are crossings out and there are drawings in the margin and doodles. There is just this grind and it goes back to this idea of “making” a poem. My old agent said, “You shouldn’t be publishing these poems because it shows failure” and I said, “It’s not about failure, it’s about process” and he was actually very interested in process and I think he kind of came around to this idea. I think we like to have things presented as finished articles, but the performance of a poem is always different and in poetry there’s a lot of work that you don’t get to see, it isn’t always about misery and failure and rejection, and there is in fact a beauty to these little fragments. For example, I recently took a line from a poem I wrote and rejected ten years ago and used it in a new poem. It’s like that little picture on the contact sheet: keep that for next time!

Il sito di Jan Noble